Indian farmers also want regulation, no surrender to the free market.

Article translated from the summary made by Greet Goverde for Platform ABC (link for Dutch text).

The Peasant Foundation recently organized a discussion about the farmers’ protests in India, more on that below. But first the background: why protests, why now? It is actually a struggle against liberalization that is only now looming in India.

Farmers from India’s northern states marched through the five main access roads to the capital, Delhi, in November, but were greeted with tear gas and water cannons. At those access roads they have set up camp and they are still there – for six months already. All because Prime Minister Modi’s government has promulgated 3 new agricultural laws that will totally change the agricultural practice for many decades. The repercussions of those laws in a country where half the population is employed in agriculture could be disastrous.

Farmers from India’s northern states marched through the five main access roads to the capital, Delhi, in November, but were greeted with tear gas and water cannons. At those access roads they have set up camp and they are still there – for six months already. All because Prime Minister Modi’s government has promulgated 3 new agricultural laws that will totally change the agricultural practice for many decades. The repercussions of those laws in a country where half the population is employed in agriculture could be disastrous.

In the 1960s, India as a newly independent country could barely produce enough food. A series of dry summers caused famines. The government modernized agriculture and launched the “Green Revolution”. American experts were brought in to boost wheat and rice production, but too much fertilizer and pesticide and irrigation were used, making large tracts of land infertile. Many crops did poorly, with some traditional crops disappearing altogether. But rice and wheat yields increased massively, and soon the food shortage turned into a surplus.

In these circumstances, India developed a food marketing system to ensure fair prices. It is a complex system and varies from state to state but mainly boils down to this:

Farmers bring their harvest to wholesale markets called “mandis”. There, farmers sell their produce to traders in public auctions at transparent prices. Prices are also influenced by the MSP system: Minimum Support Price, a government price for crops such as rice, cotton and wheat. The government only buys a few harvests per state but those sales serve as a target price. From there, the harvests go to a second-tier market, or they are stored by the buyers for a time before being sold on.

It’s not a perfect system. At the end of the chain, local traders often collude and there is no real competition, but overall it works because there is oversight and the farmers know what the target prices are. And the goal is to help the farmers , who are the weakest link and can be exploited in many ways. Through this system they are protected, although it can vary from state to state. In Punjab and Haryana, farmers have the highest incomes in the country, but in Bihar the markets were abolished back in 2006 and that’s where the poorest farmers in the country live.

In recent years there has been another crisis: money is disappearing from agriculture, and more than half of the farmers are deeply in debt, which has led to many suicides: 20,000 in the last two years. That is why farmers have been asking for reforms for decades. But not the reforms that the government has now started, on the contrary! The ‘minimum support price’ is being abandoned, and they do not agree.

DEREGULATION

Three laws have been passed, and all three deregulate a different part of the system:

The first law creates free unregulated opportunities for (wholesale) trade outside the markets/ mandis, directly between the farmer and the wholesaler/middle man. This creates two parallel markets with very different rules. One with target prices and one in which large companies are given room to trade unregulated. The traditional trading environment (the ‘mandis’) will collapse.

The second law sets rules for ‘contract farming’, mutual agreements on the sale of the harvest between farmers and traders, where the farmers need to take the price and have no defense against ‘bad deals’.

The third law deals with another part of the chain: storage. Storage quantities were first limited but now one can store unlimited quantities – and keep them until a time of higher prices. Speculation on prices increases, in other words.

These three laws are actually inviting big players into this fragmented and deregulated market. . This could well lead to very volatile prices for farmers. Basically, the government is saying with this that farmers no longer need protection.

These reforms were announced on June 3, 2020, and the results quickly became apparent. The ‘mandis’ are already noticing that fewer harvests are being offered, and in the state of Madhya Pradesh, 40 markets have already been shut down. Trade has shifted, but farmers are not getting better prices.

This is the context of the farmers’ anger, They didn’t get what they asked for.

We feel betrayed, the farmers say. We are fighting for our rights. We have learned from our parents and grandparents, and we are passing on our lessons to future generations.

The info in this piece comes largely from a video by Christine Thornell and Pritti Gupta:

note 1: actually they have the same demands as EMB, Oxfam and FOEE and other organizations: regulation! See previous post on our website.

note 2: recently a report came out by Indian scientists: Interrogating the Food and Agriculture Subsidy Regime of the WTO. It states that it is not fair that the US and the EU since 1995 (Agreement on Agriculture) get away with subsidizing agriculture, while poorer countries like India are not allowed to, purely because of the preponderance of the richer countries in the WTO. Some quotes from the report:

(p. 17) “while developed countries subsidise their agricultural sector for exploiting global markets, large developing countries use agricultural subsidies essentially to ensure domestic food security and to promote rural livelihoods”

(p. 18) “Developing countries, therefore, need to initiate steps to amend the principles on which the AoA has laid down the subsidies’ disciplines, and to also ensure that subsidies contribute to the realisation of the twin objectives of food security and rural livelihoods in developing countries. Real reforms in the agricultural subsidies can only occur if the AoA is able to prevent the agri-business to continue its expansion using support from their home governments.”

===============================

WEBINAR “INDIAN FARMERS PROTESTS” BY BOERENGROEP/PEASANT FOUNDATION AND VOEDSEL ANDERS

scroll down to watch the recording of the webinar

Some points from the webinar organized by Boerengroep and Voedsel Anders, with contributions from G. Ramanjaneyulu of Centre for Sustainable Agriculture, and Vidya Dinker, Indian Social Action Forum (INSAF).

India is a federation of states. The states implement federal laws in different ways: some states allow out-of-state sales, others do not; ‘contract farming’ began in some states as early as the 1980s, in others later or not at all; some states regulate tenders, others do not. That created unequal treatment. All farmers now want to get rid of the restrictions on storage, but they want to keep the fixed prices. For this, they cannot go to court: there is a ‘dispute settlement’ established by law, where they usually lose. In Punjab, the government has forced farmers to grow rice and wheat, which require a lot of water. There are many problems there and that is where the protests began.

Once the protests began, they caught on. In October, there were sit-ins everywhere, and in November, people from three states in particular flocked to Delhi. A new type of farmer had emerged: determined. This surprised even the traditional peasant leaders. On January 26, Republic Day, they went into town with their tractors. The government wanted to direct them to a park but they went back to their camps near the roads. 11 rounds of talks yielded nothing; the farmers stuck to their demand: repeal those three laws. The government and some media mocked and taunted the farmers, thinking that the protests will end with the freezing winter. The farmers sat under canvas tarps but did not know what to do. If our grandfathers held out against the British for 9.5 months at the beginning of the century to get land rights, can’t we hold out for 3.5 months? Now comes a blistering hot summer, but still they stay. (As many as 280 people have died, in some cases from the cold).

The government has detained farmers and journalists and lawyers for sedition, but resistance is actually growing, including in other states. In late January, the camps had their water cut off, no toilets, barbed wire everywhere, no food allowed in, and electricity cut off. But farmers are digging latrines and wells, they are getting solar panels and generators, and they are holding back “lapdog media”(“lapdogs-of-the-government media”). Food is smuggled in by women, who help cook. Young people organize the social media campaigns. Now the protests have spread across the country: traditional village councils have evolved from anti-woman gossip circuits to action centers. There are non-violent protests everywhere according to the best traditions of the country.

Women make up 65% of the peasantry but they were rarely given a voice. Now they count and they make sure that they are also portrayed on posters. On March 8, 90,000 women stood at one of the state borders: it was a sea of yellow, the color of the mustard fields. Farmers’ organizations and trade unions (until now strongly linked to the various political parties) also expressed their support, as did Navdanya, the organization of Vandana Shiva.

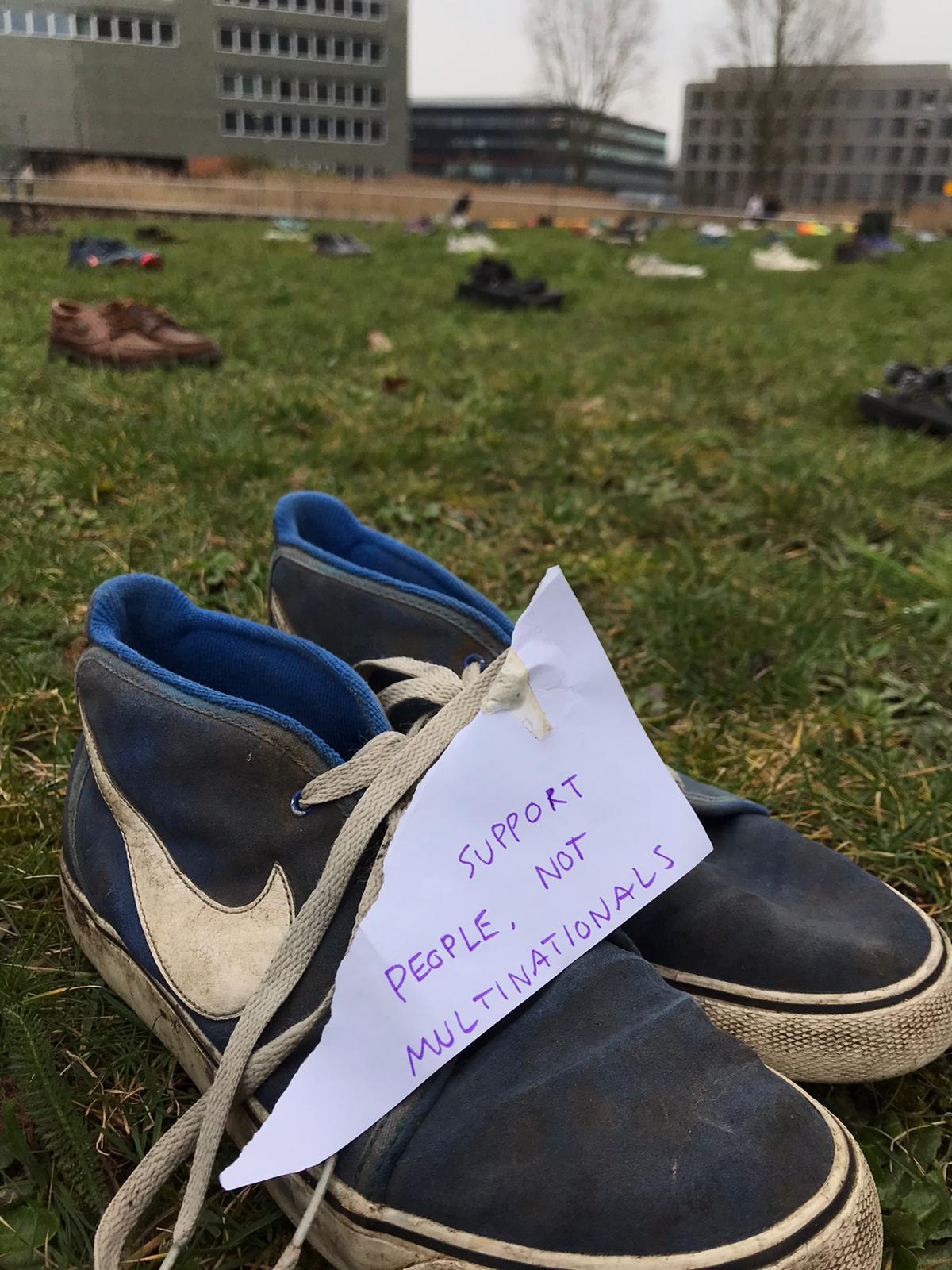

There have already been protests in the Netherlands; Extinction Rebellion, for example, protested at the Indian Embassy. Those present at the webinar are still considering how we can show solidarity. At the Wageningen campus, a solidarity action took place on the same day as the webinar, to grow awareness about the problem, and make the link to issues in this part of the world.

Watch the webinar below. If you want to help subtitle the webinar, please send an email to st.boerengroep@wur.nl.