We live in a world where 1 out of 9 people suffer from hunger – some 815 million people in total. Eighty percent of them live in rural areas and are directly dependent on agricultural practices: small scale farmers (“peasants”), landless rural workers, fishers, shepherds, pastoralists, hunters and gatherers etc. (FAO 2017 ; Tittonell, 2015). While ‘we’ need to feed the growing population, the food producers themselves are under enormous pressure – also in a modern country like the Netherlands.

By: Elske Hageraats

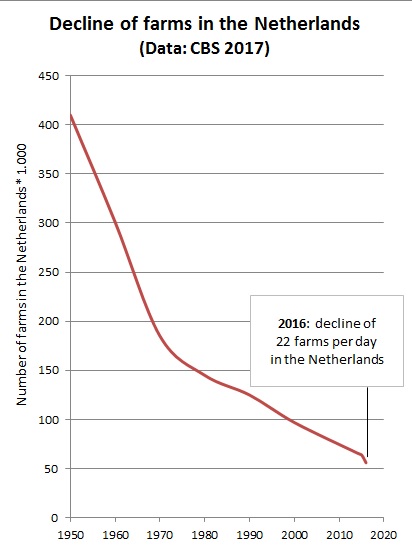

While we are talking about ‘feeding the world’, more and more rural workers are leaving the land – often by force (be it actual violence or strong economic pressure). The Netherlands –the example of a ‘developed country’, full of ‘modern agriculture’ – certainly does not escape this trend: in 2016, this country alone has lost 22 farms every single day (CBS, 2017). They don’t go bankrupt because of a lack of modern technologies – we are one of the leading countries in terms of agricultural technology. Neither do they go bankrupt, because they don’t have access to proper schooling, infrastructure, or good soils – the Netherlands has it all. There are other factors playing a role: the prices farmers obtain for their produce are decreasing (sometimes even below the cost of production), while the costs are increasing more and more. Meanwhile the competition from the world market has never been felt so strong.

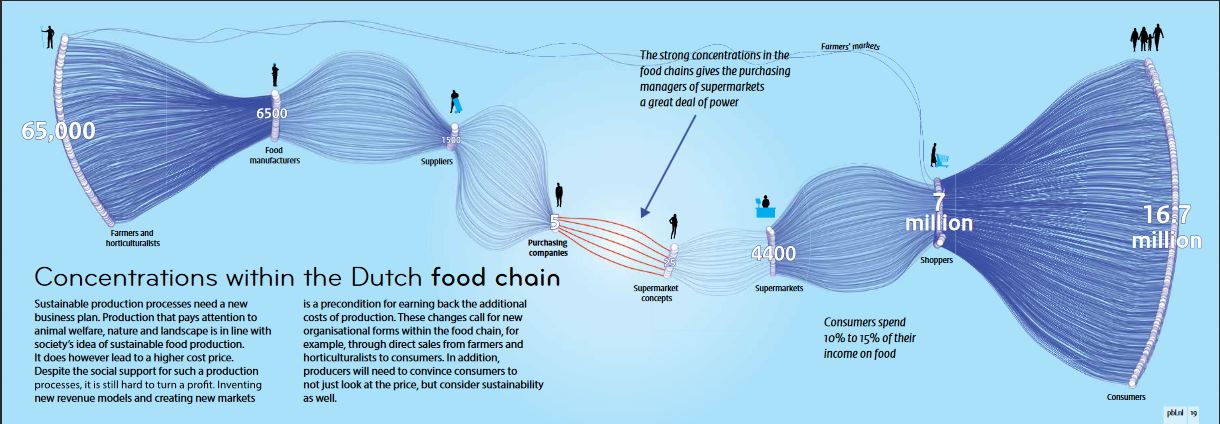

Supermarket concerns attract consumers to their shops with cheap prices and special offers, which they can offer due to the low prices they give to farmers. Example: while the consumer pays €1,85/kg Milva potatoes, the farmer received only €0.10/kg (foodlog, 2017). Likewise, big companies like Friesland Campina had a profit of € 362 million in 2016 (Friesland Campina, 2017), while the dairy farmers received a milk price below the cost of production in that same year (Foodlog, 2016). Vegetable growers show how the supermarkets paid them a price below the cost of production and afterwards sold the produce for a discount price in order to attract consumers. (Here an example interview from Belgium, but same holds true in the Netherlands: Wervel). Farmers are unable to compete within the world market. The strong concentrations in the food chains gives the purchasing managers of supermarkets a great deal of power (see picture below).

Because of decreasing prices for their produce, farmers are forced to get a loan from the bank. But banks (like Rabobank) often only provide a loan when the farmer agrees to scale up, have more animals and to sell the produce to specific companies. “For the bank it’s all about kilo’s per hectare, not about sustainability“, says farmer Rick Huis in ‘t Veld (Drion, 2017). Some examples from the Netherlands: an average pig farmer had around 7 pigs in 1950 – currently you can find around 1.6 thousand pigs on one pig farm in the Netherlands. The average amount of beef cattle per farm went up from 13 to almost 160 animals (CBS 2017b). More and more consumers, scientists and farmers are worried about the impact of this growth on the environment, animal welfare and food safety.

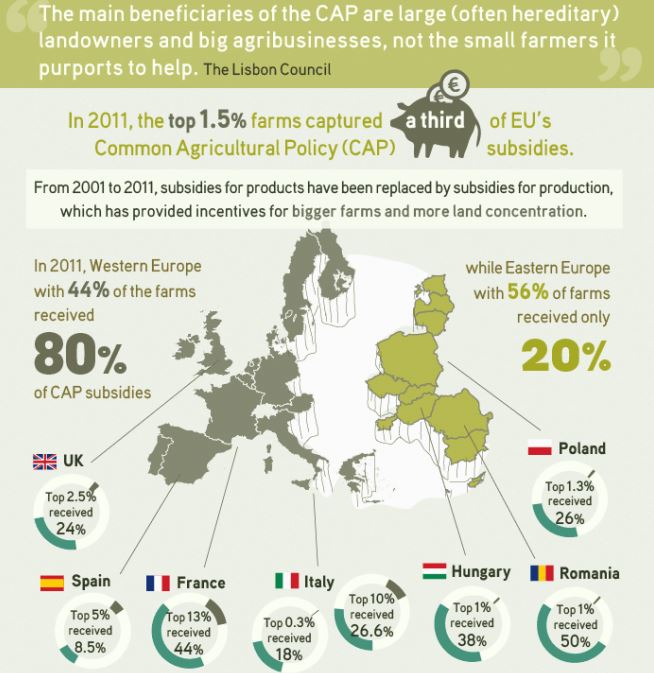

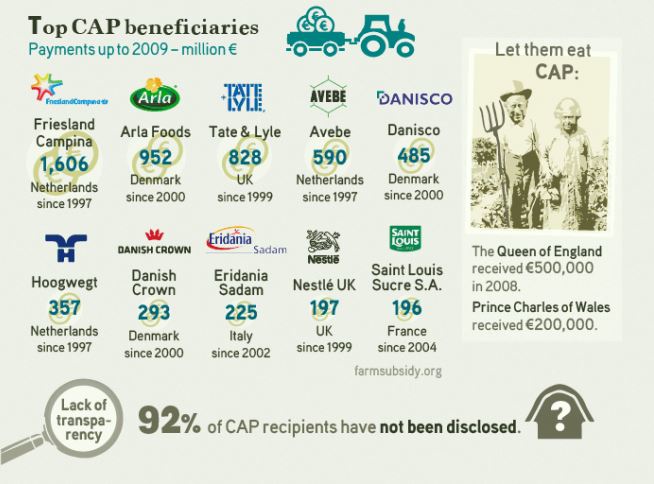

The ‘entrepreneurial agriculture’ (ondernemerslandbouw) which is embracing high-tech, industrial agriculture, is not only financed by loans from the bank: also with huge amounts of subsidies. Eighty percent of the EU subsidies go to only 20% of the wealthiest farmers, while peasant agriculture (boerenlandbouw) hardly receives any (van der Ploeg, 2017). The result of all this is that from 1950 up to now, we have lost six out of seven farms in the Netherlands (CBS 2017). How can we expect farmers to invest in the environment, animal welfare, a healthy soil, biodiversity or sustainability, if we don’t give them a fair price for their products? How can the young generation continue the farm work – knowledge and skills build up through centuries – when they cannot make a living out of it anymore?

But…

But…

Statement 1: “Why do we need farmers if we have industrial agriculture producing food to feed the growing population”

According to the UNCTAD report of the United Nations, the world currently already produces sufficient calories per head to feed a global population of 12-14 billion. (UNCTAD, 2013) So hunger is not a result of a ‘lack of food’ in the world. The point is that food isn’t produced there where it’s needed (Tittonell, 2016). One of the most important advantages of peasant agriculture, is that it can produce food crops everywhere – also in remote areas, where the food is needed most. There is a major shift from ‘food crops’ (to feed people), to cash crops (for the export to the West, e.g. cotton, coffee, soy), often financed by and lobbied for by those who shout “we” need to feed the world. This results in more pressure on the livelihoods the peasants, including the rural poor.

Statement 2: “We (the West) need to feed the growing world population.”

Let’s ask ourselves: who’s the “we”? Why can’t the world feed itself? And what do the hungry people themselves actually see as a solution? In order to find out, let’s see what they fight against.

If we want to feed the growing population in the world, it is time to listen to the rural population. While companies, governments, universities and media in the West are shouting that ‘we’ need to produce more food (often with technological innovations they are developing) – there are totally different demands from those who actually suffer from hunger: the rural workers. 500 people from more than 80 countries came together: peasant farmers, fisherman, shepherds, pastoralists came together to let their voices be heard and write a declaration, they named the Nyeleni Declaration. In this declaration they didn’t ask the West for more food. Neither did they ask for expensive technological innovations. In fact, technological innovations and food aid are even mentioned as cause of poverty and hunger. The people call to join the movement and fight for voedselsoevereiniteit, and against:

- Technologies and practices that undercut our future food producing capacities, damage the environment and put our health at risk. These include transgenic crops and animals (GMOs), terminator technology, industrial aquaculture and destructive fishing practices, the so-called White Revolution of industrial dairy practices, the so-called ‘old’ and ‘new’ Green Revolutions, and the “Green Deserts” of industrial bio-fuel monocultures and other plantations;

- The privatization and commodification of food, basic and public services, knowledge, land, water, seeds, livestock and our natural heritage;

- The dumping of food at prices below the cost of production in the global economy. Providing a country with cheap food sounds good, but it’s destroying the livelihood of the poor: the peasant farmers;

- Food aid that disguises dumping, introduces GMOs into local environments and food systems and creates new colonialism patterns;

- Imperialism, neo-liberalism, neo-colonialism and patriarchy, and all systems that impoverish life, resources and eco-systems, and the agents that promote the above such as international financial institutions, the World Trade Organisation, free trade agreements, transnational corporations, and governments that are antagonistic to their peoples;

- The domination of our food and food producing systems by corporations that place profits before people, health and the environment;

- Development projects/models and extractive industries that displace people and destroy our environments and natural heritage;

- Wars, conflicts, occupations, economic blockades, famines, forced displacement of peoples and confiscation of their lands, and all forces and governments that cause and support these (example: Syria; see also this article Agriculture and Food Sovereignty in Syria, 2017)

- Post disaster and conflict reconstruction programs that destroy our environments and capacities;

- The criminalization of – and violence against – all those who struggle to protect and defend our rights (example: Colombia, Honduras,..);

- The internationalisation and globalisation of paternalistic and patriarchal values, that marginalise women, and diverse agricultural, indigenous, pastoral and fisher communities around the world;

Statement 3: “Surely small-scale organic agriculture cannot feed the world… It’s so ‘backward’ and a romantic illusion”

FAO’s SOFA report (2014a) estimated, based on an analysis of just 30 countries, that there are approximately 500 million family farmers in the world who produce 80% of the world’s food. It is also often stated that this production takes place on only 20% to 30% of the agricultural resources like land – and generally in less productive, marginal environments (ETC 2013). One of the most important advantages of peasant agriculture, is that it can produce food crops everywhere – also in remote areas, where the food is needed most. If we talk about sustainable agriculture that can keep on feeding the world, the small scale peasant farmer might just be the big example for all of us.

Moreover, we need to realize that agriculture is not only about producing food. There’s the word ‘culture’ in agriculture: it means a rich way of life is connected to working the land. Besides providing food, agriculture is also about:

- keeping alive the genetic biodiversity by growing hundreds of varieties that are adapted to that specific soil, climate, altitude, ecosystem.

- Breeding new varieties

- Keeping alive all the knowledge and skills that have been build up throughout centuries, passed on from generation to generation

- Building up healthy soils, feeding the soil life

- Mitigation of climate change by storing carbon in the soil and minimizing the carbon emission by a minimized transport of food

- Building up rich ecosystems with many species of plants, animals, insects, and soil life

- Creating jobs. Of all the 280.584 people still working in agriculture in 2002 in the Netherlands, some 39% have lost heir job (CBS 2017).

- Creating a lively countryside

- Keeping alive the culture of that place (which is often intimately linked to the land)

- Educating young people who’d like to work with peasants or become a peasant themselves

- Autonomy and freedom of the people. Like Samih from Syria explains: “One of the most important ‘weapons’ used by the Syrian regime to smash the revolution is hunger, knowing that most of the besieged areas within the country are rural areas (…) Agriculture means independence and control – and this, in turn, means greater freedom and thus greater dignity.”

Karam adds: “Before the war, if someone wanted to cultivate certain crops, they would go to a so-called “farmers’ pharmacy” to pick up hybrid seeds, chemical fertiliser, etc. Today, we have come to realise that, as far as seeds, fertiliser, and pesticides are concerned, it is better to be self-reliant. Many people see it that way now.” (Jasim, 2017).

Statement 4: “Anyway, young people don’t want to start in agriculture..”

Despite the many challenges, we see more and more young people who want to continue / start in agriculture (ILEIA, 2011). We see an enormous incline in students at the Warmonderhof (school for practical bio-dynamic farming; see also their MAP). Below, you see a picture of Toekomstboeren (“Future Farmers”), a member of the world wide organization La Via Campesina. Toekomstboeren is a growing organization that wants to inspire people: it is possible to start a farm – even when it’s an organic, small scale peasant farm.

Toekomstboeren are young people who (want to) start a sustainable form of agriculture, but often find many challenges:

- access to land. The price of one hectare of agricultural land in the Netherlands is around 80.000 euro – sometimes even 120.000 euro.

- access to knowledge. This generation of young (future) farmers is often not raised at a farm. Many years of industrialisation of agriculture is threatening the survival of skills and knowledge, which were build up for centuries and passed on from generation to generation. A loss of farmers means a loss of knowledge..

- access to finance. Banks in the Netherlands only provide loans if you have a business plan that suits their vision (which is so often big scale industrial agriculture)

- access to the market. With supermarkets providing such cheap food, how can we convince our consumers to buy in our farms, so that a fair amount of the money goes to the producer?

Despite these challenges, people still find creative ways to make it work. Some examples are the various forms of Community Supported Agriculture (CSA), like:

- self-harvest gardens (consumers harvest their own food) e.g. http://www.denieuweronde.nl/

- memberships (consumers pick up a box with food from the farm or a pick-up point at a nearby city every week). E.g. http://www.ommuurdetuin.nl/

- Herenboeren (a group of consumers own a farm together, and hire a farmer to work for them) http://www.herenboeren.nl/

CSA entails multiple benefits:

- A shared risk. When harvests are good, consumers get a bit more, when harvest are less good, they get a bit less – while the income of the farmer is always secured.

- Money at the start of the season, not at the end: consumers pay the money up front, so that the farmer already has the money to invest in seeds, compost/manure, seedlings etc.

- A fair price to the peasant farmer. All the money goes directly to the farmer, so no money is taken by middle man.

- The farmer – not the supermarket – sets the price (a fair price), decides what to produce (e.g. many different varieties), and sets the criteria (cucumbers don’t have to be perfectly straight, for example).

Since 1950, we have lost 6 out of 7 farms in the Netherlands alone. The farmer cannot invest in healthy food production, the environment, biodiversity, animal welfare or a healthy soil as long as the consumer doesn’t make an effort to give a fair price to to producer. Eating is a political choice: you stimulate where you give your money to. It’s that simple. Join the movement, buy your food from local farmers, join a CSA or start a Herenboeren initiative, because we cannot feed the world without peasant farmers.